Getting the lowest price for injection molded parts, without sacrificing quality.

Think like a molder

All customers want the lowest price possible, so how do you get it? You think like a molder and address the concerns that affect pricing.

What is the price the customer is seeking? Target pricing is a goal/challenge that is a good first step. The molder then considers what is it going to take to make that happen, rather than what do we guess the customer wants. A goal if you will.

Am I getting all of the information I need? How well does the customer communicate their specific needs? Are cosmetic requirements, reasonable tolerances, and other specifications appropriate for end use, and in what environment?

Consider the redesign

How much redesign will it take to achieve the goals? Will I have access to engineering to answer questions regarding quality issues, material selection, and cost reduction programs? Are there budgets available for testing alternative materials? This aspect of arriving at pricing goals is generally overlooked. When an engineer specifies a material it is often because of a few parameters. First no one wants failure during the life of the product, so the inclination is to over specify from a viewpoint of what has been working on similar applications.

Choosing certain materials can lower the price of your parts

When the quantities are modest, long-term testing probably is less cost effective than jumping up from, say, a polypropylene to a nylon with a little bit of cost increase. Long term testing might show polypropylene would work just fine, but testing cost would be prohibitive, and lead times increase. When the molder uses larger quantities of nylon, and would need to pay a premium for low quantities of polypropylene, the answer gets muddier.

Is the customer receptive to looking at materials currently being used on a daily basis to keep prices and deliveries controllable?

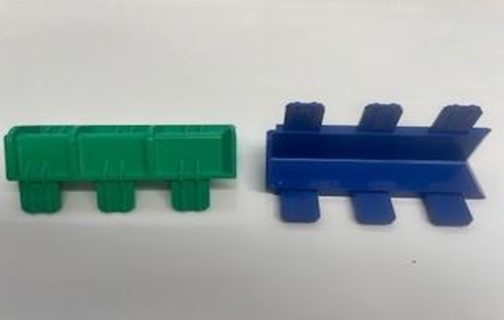

Are there expensive brass inserts in the design? Can they be replaced with inexpensive square nuts?

Wall thickness is a factor

The common method of looking at a part as a machining operation is just the reverse from designing as a molded part. The first method is removing material from a solid block, the other is defining the working surfaces and supporting them with structural features. When wall thickness is kept identical, the differential shrinkage due to different walls and accompanying warpage is minimized. When walls are too thick, higher pressures are needed to keep the part void free, resulting in greater stress. When walls on a single part are both thin and thick all kinds of problems can surface. This is why molders always ask for coring: thicker walls always add cost. Both material cost and processing cost (longer cycles for cooling). Sometimes the reason for a thicker wall is stiffness, which is true but can be also achieved by using stiffening ribs or walls, or with glass fiber in the resin.

Sometimes the thicker walls are perceived for impact strength, which isn’t always the case. Consider a thin wall soda bottle, versus a thick wall bottle of the same design. The thin wall will flex rather than break; clearly elongation is the important consideration. I once heard from the manufacturer of Ultem that a wall of greater than 3/16” with 30% glass filled Ultem would not be beneficial in any way to part design. It would be more expensive, it would not have better impact strength, or if properly designed, be any stronger. I believe this is a good general statement for any molded part. Requiring that thickness causes voids to develop, stresses get higher, and cost climbs with material cost and processing times.

How to add value to the initial part design being quoted

When the design seems complete, can we integrate other attached components into the part? How about other “free” features such as part number, or instructions for example ”uses 10-32 bolt”. Can assembly be made easier by longer lead ins on the holes for screws? Have we included radii to all inside corners to improve impact strength, and reduce stress risers?

What will the working relationship be with the QC department? Do they react appropriately to the issues? When a shipment of 100,000 parts uncovers one “short shot”, will the molder have to spend hours with a returned part, root cause analysis, paperwork that is often inadequate in the eyes of the QC representative, and a fine as punishment? A symbiotic relationship works much better.

Don’t forget the packaging

Then there is packaging: Can we use returnable or disposable packaging materials? The packaging cost for 10 large parts in a $2.50 cardboard carton is much more expensive than one hundred in a disposable gaylord.

Can quarterly purchase orders with monthly releases work?

Has this existing customer, or will this new customer provide adequate lead times, or will every order be an emergency? How much inventory will I need to maintain to meet lead times?

How does the customer pay their invoices? 10 day payment terms always reduce costs.

Bottom line is it all comes down to understanding both parties’ needs and expectations, and how the cultures complement each other.

.50 cardboard carton is much more expensive than one hundred in a disposable gaylord.

Can quarterly purchase orders with monthly releases work?

Has this existing customer, or will this new customer provide adequate lead times, or will every order be an emergency? How much inventory will I need to maintain to meet lead times?

How does the customer pay their invoices? 10 day payment terms always reduce costs.

Bottom line is it all comes down to understanding both parties’ needs and expectations, and how the cultures complement each other.